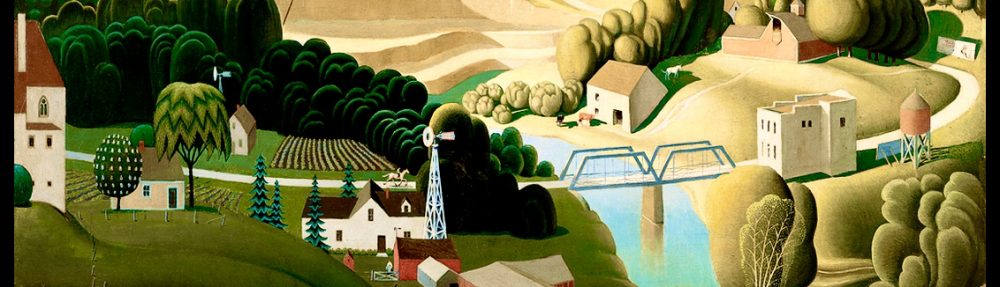

George Washington Carver was born on a 240-acre farm belonging to Moses and Susan Carver, located near Diamond (Grove), Missouri (see map above). While the exact date is unknown, it’s thought that George was born in January or July of 1864, when Missouri, as we’ve discussed in other posts, was still a Slave State (see diagram below).

Nine years prior to George’s birth (October 9, 1855), Moses Carver, a German-American immigrant, purchased George’s parents, Mary and Giles, from William P. McGinnis for $700. Apparently, Giles died in a log-hauling accident sometime prior to George’s birth, but not before Mary had given birth to several children, including a brother named James, several sisters (names unknown), and George.

When George was only one week old, he, his mother, Mary, and his sister were kidnapped from the Carver farm, with only James escaping the abduction. Night raiders, a common thing in Missouri during the Civil War-era, would steal slaves, re-selling them to land owners in the deep South. Immediately after the raid, Moses Carver hired a neighbor, John Bentley, to retrieve his “property,” but Bentley was only successful in locating George in Kentucky, whom he retrieved for Carver in turn for one of Moses’ finest horses.

After slavery was abolished (1865), Moses Carver and his wife, Susan, raised George and his older brother, James, as their own children. They encouraged both young boys to continue their intellectual pursuits, and, as George tells the story, “Aunt Susan” taught him the basics of reading and writing. As the children grew, brother James gave up his studies and focused on working the fields with Moses, while George, a frail and sickly child who could not help with such work, learned how to cook, mend, embroider, do laundry and garden, as well as how to concoct simple herbal medicines. At a young age, Carver took a keen interest in plants and experimented with natural pesticides, fungicides and soil conditioners. He became known as the “the plant doctor” to local Missouri farmers due to his ability to discern how to improve the health of their gardens, fields and orchards.

Blacks, of course, were not allowed to attend public schools, so George (age 13), in his determination to go to school, walked 10 miles south of the Carver farm to Neosho, where there was a small school for blacks. As the story goes, when George reached the town, he found the school closed for the night, so he slept in a nearby barn. The next morning he met the barn’s owners, Andrew and Mariah Watkins, a childless African-American couple who gave this stow-away a roof over his head in exchange for help with household chores. At their first encounter, George identified himself to Mariah as “Carver’s George,” just as he had done his whole life. But Mariah quickly corrected him, saying…

From now on, George, your name is not ‘Carver’s George, but ‘George Carver.’

A midwife and nurse, Mariah Watkins imparted many things to George over the next year, including her broad knowledge of medicinal herbs and her devout faith in God. In his later years, Carver often recounted a life-giving phrase he learned from Mariah…

You must learn all you can, then go back out into the world and give your learning back to the people.

At age 14, because he wanted to attend an academy there, George moved to the home of another foster family, in Fort Scott, Kansas. After witnessing the killing of a black man by a group of whites (1879), Carver soon moved on, attending a series of schools before earning his diploma at Minneapolis High School in Minneapolis, Kansas (1880). Over the next few years, George tried to further his education, and finally, after being rejected time and time again because of his color, he was accepted at Highland College (1885). That fall, when George arrived to start school, he was once again rejected, only after the school administration “discovered” that he was black.

After a year of work in Highland, (August 1886), Carver traveled by wagon with J. F. Beeler from Highland to Eden Township in Ness County, Kansas. There, he homesteaded a claim near Beeler, maintaining a small conservatory of plants and flowers and a geological collection. Without the assistance of domestic animals, George plowed 17 acres of the claim, planting rice, corn, Indian corn and garden produce, as well as various fruit trees, forest trees, and shrubbery.

In 1888, a white couple from Winterset that George had befriended through his church relationships, encouraged him to come to Iowa to pursue higher education. Despite his former setbacks, George obtained a $3,000 loan at the Bank of Ness City, relocated to Iowa, and by 1890, was enrolled at Simpson College, a Methodist school in Indianola that admitted all qualified applicants.

George initially studied art and piano in hopes of earning a teaching degree, but his art teacher, Etta Budd, recognized Carver’s talent for painting flowers and plants, convincing him to study botany at Iowa State Agricultural College in Ames. He transferred there in 1891, the first black student and later the first black faculty member at what is today, Iowa State University. As the story goes, it’s in Ames, where George, in order to avoid confusion with another George Carver in his classes, began to use the name George Washington Carver.

At the end of his undergraduate career in 1894, recognizing Carver’s potential, Joseph Budd and Louis Pammel convinced Carver to stay at Iowa State for his Master of Science degree. While in Ames, Carver performed research at the Iowa Agriculture and Home Economics Experiment Station under Pammel from 1894 to his graduation in 1896. It is this work in plant pathology and mycology that first gained George national recognition and respect as a botanist, which then led to several offers of employment.

While George might have found success at any of these job opportunities, it was the offer from Booker T. Washington of Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) in Alabama that caught his attention.

Washington was convinced that Tuskegee needed an agricultural school, yet the school’s trustee’s were hesitant. Only when Washington introduced them to G.W. Carver did they agree to the idea, and as the saying goes; the rest is history. George accepted their offer in 1896 and would work at Tuskegee Institute for the rest of his life (47 years).

For George, starting an agricultural school was not easy. First of all, in Alabama, training in agriculture was not popular — Southern farmers believed they already knew how to farm and students saw schooling as a means to escape the farm. Additionally, many faculty members at Tuskegee resented Carver for his higher salary and his unusual demand to have two dormitory rooms, one for him and one for his plant specimens!

George also struggled with the demands of the faculty position he was appointed to. He wanted to devote his time to researching agriculture for ways to help out poor Southern farmers, but he was also expected to manage the school’s two farms (for profit), teach students, sit on multiple school committees and councils, while also ensuring the school’s toilets and sanitary facilities all worked properly! Whew!

But, over the years, George had learned the lesson of hard work, so rather than complain, he simply poured himself, more and more, into his job.

Through his dedication to the eight principles listed above, Carver found great success both in the laboratory and throughout the surrounding community. Here are just a few practical examples:

George taught poor farmers in the South that they could feed their hogs acorns instead of commercial feed, and that they could enrich their croplands with swamp muck instead of buying expensive fertilizers.

Knowing busy farmers wouldn’t come to him for counsel and advice, George invented the Jesup wagon, a kind of mobile (horse-drawn) classroom and laboratory that he used throughout the area to demonstrate, first hand, the benefits of good soil chemistry.

And speaking of chemistry, George’s idea of crop rotation was revolutionary, saving the economy of the South when the one crop the region had long depended upon (cotton) finally ran its course, depleting farmers’ soil to the point of no return.

Which now, brings us to peanuts…

I must insert here, there’s a part of George Washington Carver’s success story that’s often left out. In truth, over the years, George always credited his deep spirituality as playing a huge role in his life of science. In a letter to Isabelle Coleman (July 24, 1931), he wrote…

I was just a mere boy when converted, hardly ten years old. There isn’t much of a story to it. God just came into my heart one afternoon while I was alone in the ‘loft’ of our big barn while I was shelling corn to carry to the mill to be ground into meal. My brother and myself were the only colored children in that neighborhood and of course, we could not go to church or Sunday school, or school of any kind. That was my simple conversion, and I have tried to keep the faith.

It’s interesting that Carver never pushed his faith onto others, but simply believed that he could have both a strong faith in God while also trusting in science – not an either/or but a both/and. On numerous occasions, George stated that it was his faith in Jesus of Nazareth that empowered him to effectively pursue and perform the art of science. And according to his writings, it was in the midst of one of those regular conversations with God when George “discovered” an idea that transformed not only his life’s work but dramatically changed farming in America forever.

As the story goes, when George arrived in Tuskegee (1896), the cotton crop of the south was being devastated by an on-going invasion of the boll weevil. That infestation, when combined with the deteriorating soil conditions (due to the lack of crop rotation), was sending the farm economy into the toilet. One day, as George was praying desperately about the dire situation, asking God to intervene, he quieted himself. It’s at that point when George sensed God whispering to him a very intriguing question…

“George,” the Lord asked, “Have you considered the peanut?”

As Carver tells the story, it’s that holy inquiry that sent him into the laboratory, studying the possible impact of planting peanuts instead of cotton. Over the next few years, in his daily prayers, he credits a holy intervention that introduced this faith-believing scientist to over 300 different practical uses for the peanut, including milk, Worcestershire sauce, punches, cooking oils, salad oil, paper, cosmetics, soaps and wood stains. During this season, he also experimented with peanut-based medicines, such as antiseptics, laxatives and goiter medications. All the while, as farmers rotated their crops, planting peanuts instead of cotton, the boll weevil left the area while the soil nutrients came back to life!

All in all, a big win for everybody!

Throughout his career, George did similar experiments with soybeans, pecans, and sweet potatoes, always giving credit to God, believing that godly wisdom could always be found working alongside him as he labored in his Tuskegee lab. Sadly, Carver was often criticized for such talk. In 1924, The New York Times published an article entitled, “Men of Science Never Talk That Way.” In it, The Times considered Carver’s statements that God guided his research as inconsistent with a scientific approach. As it is today, many still don’t believe Science and Religion can peacefully co-exist, but thankfully, George was not put off by the criticism and simply kept going about his business.

In 1920, U.S. peanut farmers were being undercut with imported peanuts from the Republic of China. White peanut farmers and processors came together in 1921 to plead their cause before a Congressional committee hearings on a tariff. Having already spoken on the subject at the convention of the United Peanut Associations of America, Carver was elected to speak in favor of a peanut tariff before the Ways and Means Committee of the United States House of Representatives. Carver was a novel choice because of U.S. racial segregation. On arrival, Carver was mocked by surprised Southern congressmen, but he was not deterred and began to explain some of the many uses for the peanut. Initially given ten minutes to present, the now spellbound committee extended his time again and again. The committee rose in applause as he finished his presentation, and the Fordney-McCumber Tariff of 1922 included a tariff on imported peanuts. Carver’s presentation to Congress made him famous, while his intelligence, eloquence, amiability, and courtesy delighted the general public.

In the last two decades of his life, Carver lived as a celebrity to many, but his primary focus was always on helping people. He traveled the South to promote racial harmony, and he went to India to discuss nutrition in developing nations with Mahatma Gandhi. Three American presidents—Theodore Roosevelt, Calvin Coolidge and Franklin Roosevelt—met with him, and the Crown Prince of Sweden studied with him for three weeks. Up until the year of his death (1943), George also released bulletins for the public, reporting not only on research findings, but also offering practical advice for farmers, scientists, teachers, and yes, even delicious recipes for housewives.

Sadly, George Washington Carver died, at age 78, on January 5, 1943, from the consequences of falling down the stairs of his home. This amazing man never married, dedicated first and foremost to his work, and is now buried next to Booker T. Washington on the Tuskegee Institute Grounds.

Due to his frugality, Carver’s life savings totaled $60,000, all of which he donated in his last years and at his death to the Carver Museum and to the George Washington Carver Foundation. On his grave is written…

A life that stood out as a gospel of self-forgetting service. He could have added fortune to fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honor in being helpful to the world.

On July 14, 1943, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt dedicated $30,000 for the George Washington Carver National Monument near Diamond, Missouri, where he was born. This was the first national monument dedicated to an African American and also the first to a non-President. At this 210-acre national monument, there is a bust of Carver, a ¾-mile nature trail, a museum, the 1881 Moses Carver house, and the Carver cemetery.

In addition to his work on agricultural extension education for purposes of advocacy of sustainable agriculture and appreciation of plants and nature, Carver’s important accomplishments also included improvement of racial relations, mentoring children, poetry, painting, and religion. He served as an example of the importance of hard work, a positive attitude, and a good education. His humility, humanitarianism, good nature, frugality, and rejection of economic materialism also have been admired widely.

One of his most important roles was in undermining, through the fame of his achievements and many talents, the widespread stereotype of the time that the black race was intellectually inferior to the white race. In 1941, Time magazine dubbed him a “Black Leonardo”, a reference to the Renaissance Italian polymath Leonardo da Vinci. To commemorate his life and inventions, George Washington Carver Recognition Day is celebrated on January 5, the anniversary of Carver’s death.

Carver appeared on U.S. commemorative stamps in 1948 and 1998, and he was depicted on a commemorative half dollar coin in 1951. Two ships, the Liberty ship SS George Washington Carver and the nuclear submarine USS George Washington Carver were named in his honor.

In 1977, Carver was elected to the Hall of Fame for Great Americans. In 1990, Carver was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame, the first African-American to receive that honor. In 1994, Iowa State University awarded George a Doctor of Humane Letters, and in 2000, he was a charter inductee in the USDA Hall of Heroes as the “Father of Chemurgy”.

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed George Washington Carver on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans, and that same year, Carver was also posthumously given The Iowa Award, the highest honor given to a resident of our state. Click here for more info.

On the personal side, I must tell you that, over my thirty-plus years of pastoral ministry, I’ve told the amazing story of George Washington Carver to others numerous times. I absolutely love George’s ability to overcome the many struggles he faced in life, and have often encouraged young people to take George’s attitude toward their work, knowing that God is actively involved in both the sacred and the secular, empowering those like George who knew…

You must learn all you can, then go back out into the world and give your learning back to the people.

Godspeed, George Washington Carver … Godspeed.

Click here to access our Rich Stories of Diversity Timeline…

Kudos to the amazing resources below for the many quotes, photographs, etc. used on this page.

George Washington Carver, History.com, February 1, 2021

George Washington Carver, Wikipedia

God’s Scientist: George Washington Carver, Eric Guttag, IPWatchdog, February 11, 2014

George Washington Carver – February 19, 1936, 5 Fun Facts, TFH Supplies

George Washington Carver, Find-A-Grave

Click here to go on to the next section…

Click here for a complete INDEX of Our Iowa Heritage stories…